When the Crocodile Chewed Its Lungs

On the banks of the Suez Canal, almost at the canal’s midpoint, lies the city of “Ismailia.” It is one of the three Canal Zone governorates, a place that was once celebrated as the “City of Gardens,” where tree-lined boulevards and lush public spaces shaped its identity. But the city has not remained the same. Over time, the green canopies that once shaded its streets have been cut back, sacrificed in the name of urban expansion. Towering trees gave way to bridges, roads, and new concrete structures. What little remained of its historic green spaces — once symbols of leisure, beauty, and cultural memory — has been left uncared for, fading quietly under the weight of neglect.

The Crocodile and its bond with the city of Ismailia.

Long before Ismailia became known as “Ismailia,” it carried another name, one drawn from the waters that lap against its western edge: "Lake Timsah” (The Lake of the Crocodile). From this lake, rich with salt and legend, the place first took its identity. The crocodile — an animal both feared and revered in ancient Egypt — left its imprint not only on the landscape but also on the imagination of those who lived here. Thus, the early settlement was called “Timsah” (The Crocodile), a name that spoke of nature’s power and mystery.

When the city was later founded in 1863 during the construction of the Suez Canal, it was renamed “Ismailia” in honor of Khedive Ismail. Yet, beneath this official title, the echo of the crocodile remains, a reminder that the city’s roots are as much tied to myth and water as they are to history and empire.

The History of the City of Gardens.

At that time, the city resembled a “green oasis” in the heart of the desert, with trees planted and gardens landscaped to receive the European engineers and workers involved in the construction of the Suez Canal.

The “French Gardens” were established alongside broad, shaded avenues, and Ismailia became renowned for the density of its trees. During the British occupation and later under the French presence through the Suez Canal Company, the cultivation of gardens and the planting of trees continued, particularly in the “European Quarter.” Until the 1950s, Ismailia was widely described as the “City of Gardens.”

Post-nationalization of the Suez Canal.

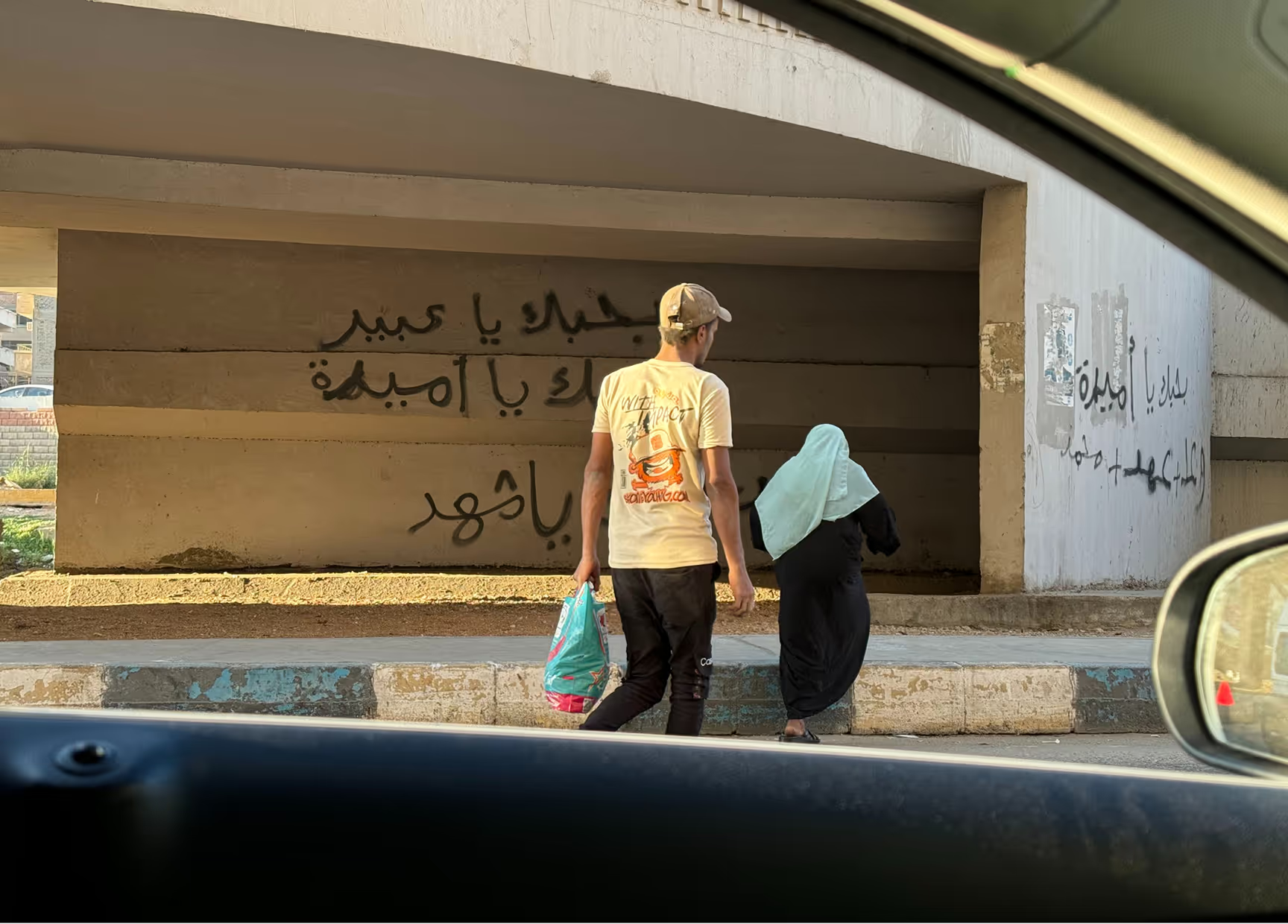

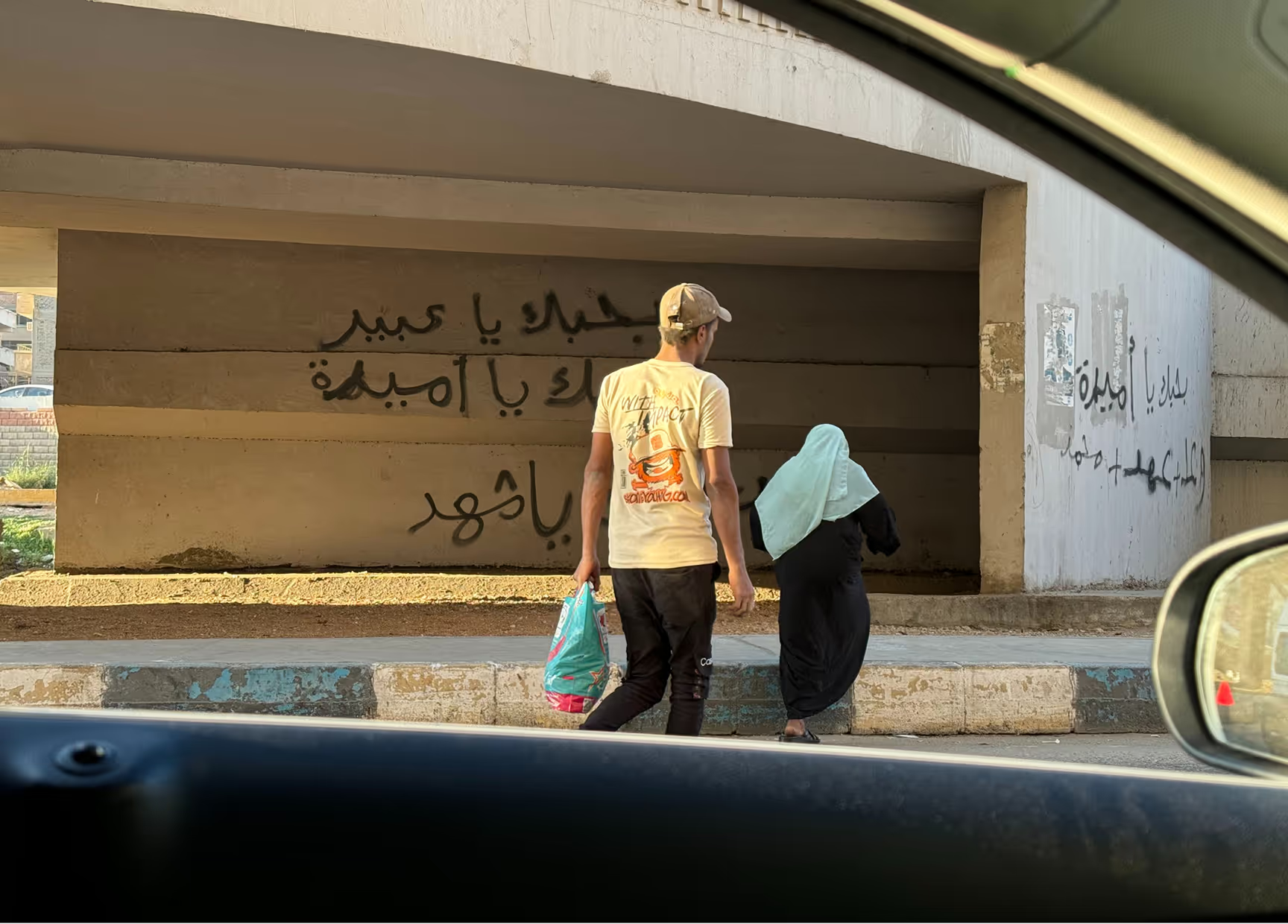

Following the nationalization of the Canal in 1956, attention to the city persisted, yet urban expansion began to encroach upon its green spaces. After the October War of 1973, reconstruction and the influx of new residents triggered a major wave of urban growth, leading to the removal of gardens and trees to make way for housing, roads, and new facilities. In the 1980s and 1990s, the construction of internal bridges further transformed the city’s green fabric.

Spanning the City: Bridges and Modern Roads.

With the dawn of the new millennium, and especially after 2010, the pace of constructing bridges and tunnels accelerated to connect Ismailia with the Suez Canal Corridor Development Project. This expansion came at the expense of green spaces, particularly along “Lake Timsah” and at the city’s entrances, where parts of the historic green belt were cleared to make way for new structures such as the “Serapeum Bridge and Bridge of Nemra 6.” The impact of urban growth extended beyond the landscape, diminishing biodiversity as certain bird and plant species once tied to the city’s orchards and gardens gradually disappeared.

Ismailia’s story, then, is not only about its past glory but also about a struggle between memory and modernization, between a city’s natural soul and the pressures of relentless urban growth.

%201.png)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)