When a city forgets its craft

by Mariam Ashraf

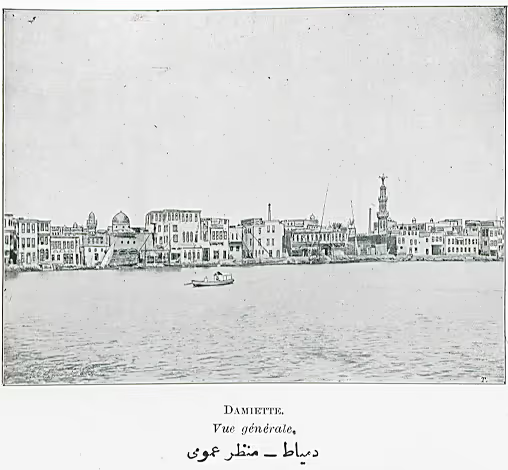

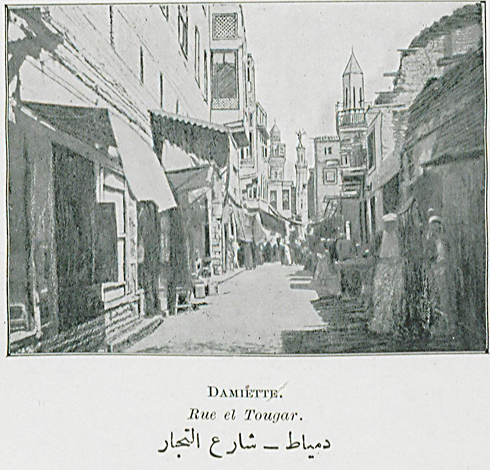

In Damietta, a city where life weaves through narrow alleyways and the scent of wood mingles with both hope and fear, the story of generations unfolds, generations raised on the art of carpentry.

Here, the craft is not merely a means of livelihood; it is an identity and source of pride. Yet, as unemployment rises and workshops some over a hundred years old shut their doors, this identity begins to erode. What once defined the people here is slowly fading, placing many livelihoods and lives at risk.

While some struggle to put food on the table, a deeper crisis brews: the loss of hope. For many, woodworking is not just a job; it is everything they have ever known. It carved their features, built their history. And when the workshops close, when the work vanishes, this loss becomes a crisis of identity. Suicide rates are rising, not out of hunger, but out of despair. Out of losing a part of themselves.

This project documents the commercial decline faced by wood traders and furniture craftsmen in Damietta, a decline that has forced many to shut down their workshops and leave behind the profession they inherited from their ancestors. Some have turned to other trades; others, unable to bear the weight of loss, have taken their own lives.

It tells the story of how a love for the craft turned into a burden, threatening both life and identity. It reveals their growing sense of abandonment, how society has marginalized them, how the trade passed down through generations is vanishing, unacknowledged. And they ask: Can a city forget its craft?

It is a story of a city, it is a story of artisanry, and it is my story too.

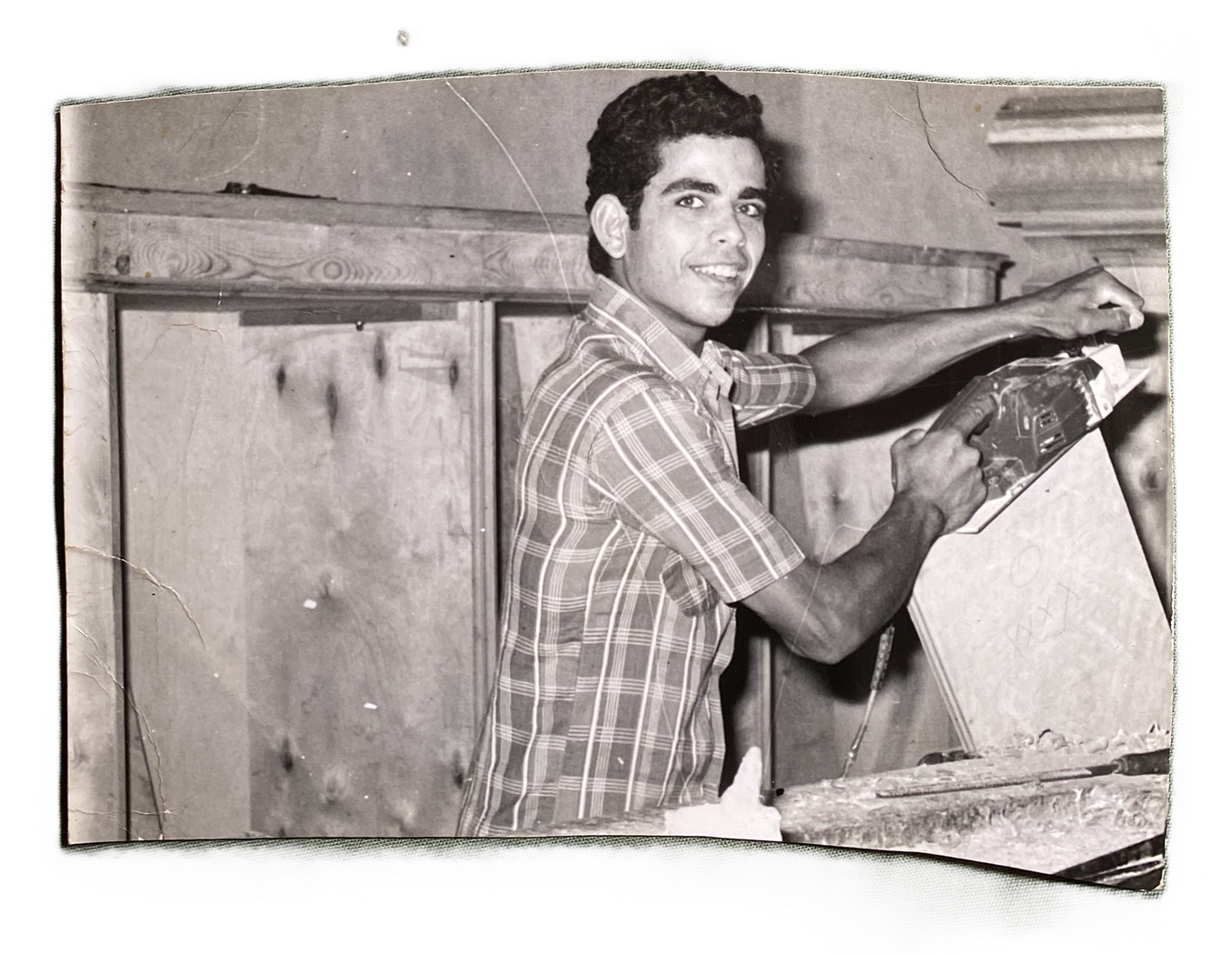

Like many born in Damiatta, the first sounds I remember as a child are the hammering of nails and the buzzing of saws slicing through wood. The scent of sawdust and raw timber filled the air. This was the backdrop of my childhood, living in the home of my uncles. For half a century, they were right in the middle of Damietta’s legendary furniture industry – mastering crafts passed down from father to son like a treasured heirloom. They were there when Damietta would produce 1% of the world's classical furniture across its thousands of workshops. My eldest uncle wasn’t just a carpenter - he was a designer, an artist in his own right. Customers would come to him from across the country.

My father's family comes from a small village called El-Khayata, one of the villages in the northern part of the Damietta governorate.

El-Khayata is known for its furniture workshops and paint-spraying shops, making it one of the prominent carpentry hubs in Damietta. Over the years, the village has seen significant development in this field.

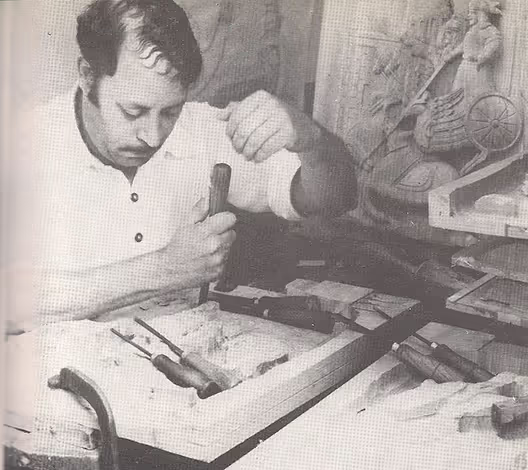

My eldest uncle, Mohamed, was among the first to take up carpentry in El-Khayata, starting his journey during the aftermath of the 1967 war. He opened a small workshop in my grandfather’s house, where he worked for seven years.

Each day, he would carry wooden planks on his shoulder and ride his bicycle, traveling long distances from the city center to El-Khayata. But due to the lack of available machinery in the village at the time, he eventually had to move his workshop to the center of Damietta.

He loved woodworking, pouring passion and devotion into his craft. In the beginning, he worked entirely by his own hand - no workers, no machines. Over time, he built a strong reputation for his living rooms and dining sets. He remained in the furniture business for nearly twenty years before shifting into the timber trade, until he passed away.

The craft was then passed down to my other uncles. At this time, if someone learned the crafts of the city, they were guaranteed work with a living wage. If someone mastered the craft, it would attract customers from across Egypt.

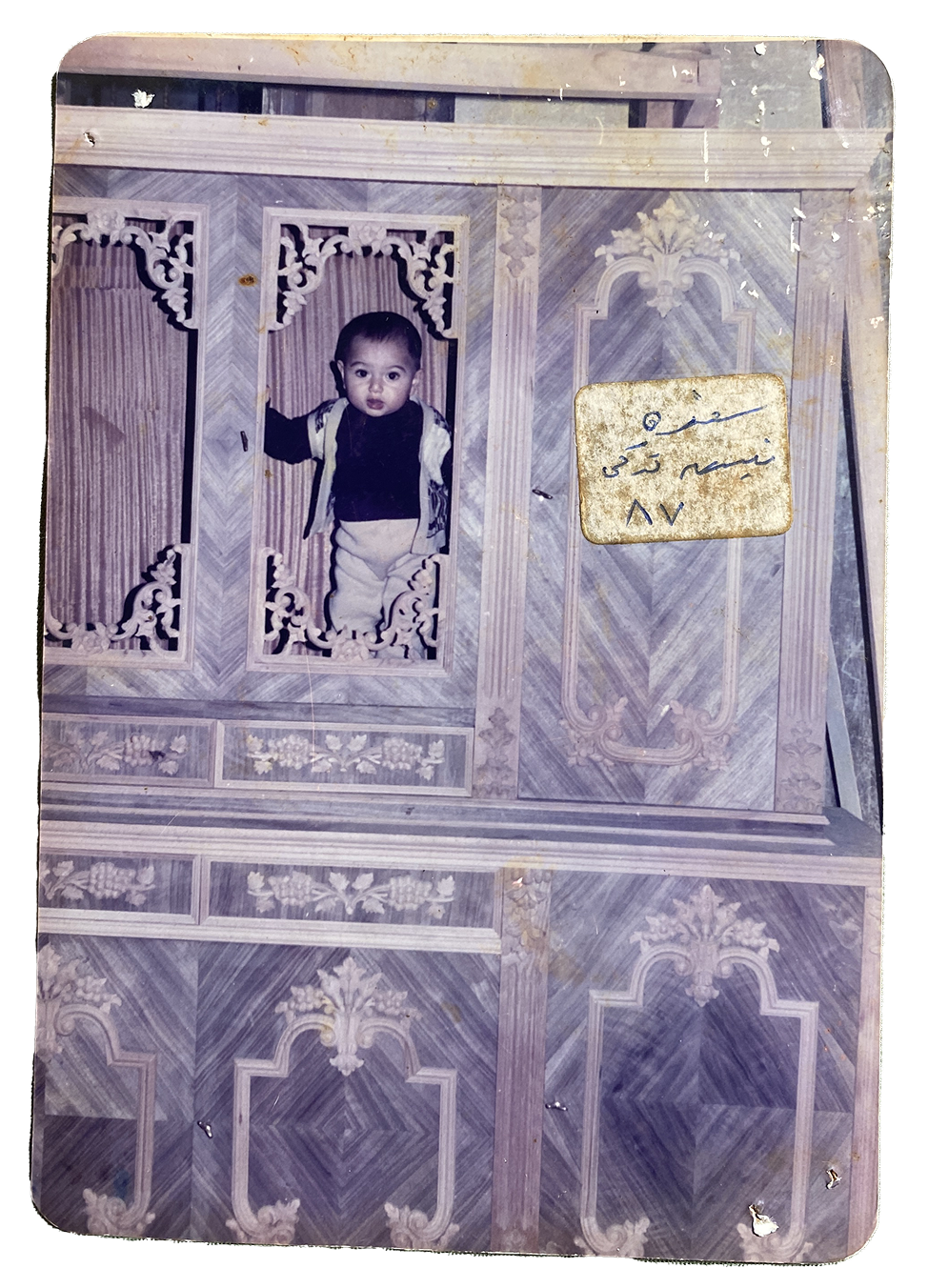

My youngest uncle, Shaker, started working in the workshop at the age of twelve, learning the trade under the guidance of my middle uncle, Hussein. He opened his own workshop in 1987, which quickly became a destination for buyers from all over the country, as my aunt Afaf explains:

“Your uncle would come home from the workshop with guests from other cities, we’d feed them and let them spend the night so they didn’t have to travel back at night… Our house was always open for everyone.”

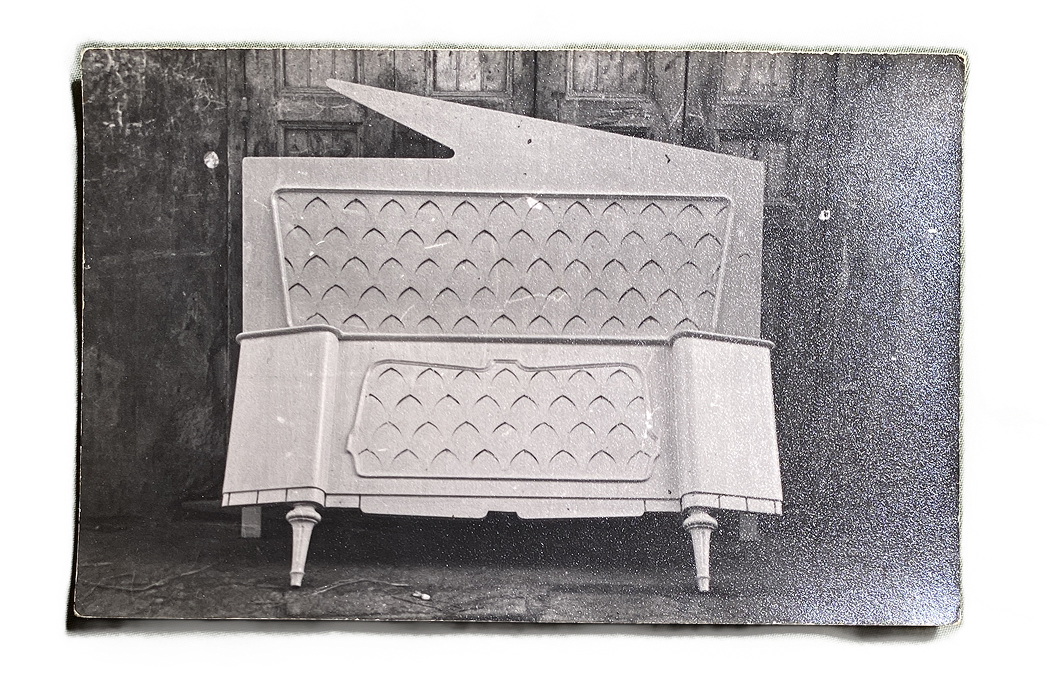

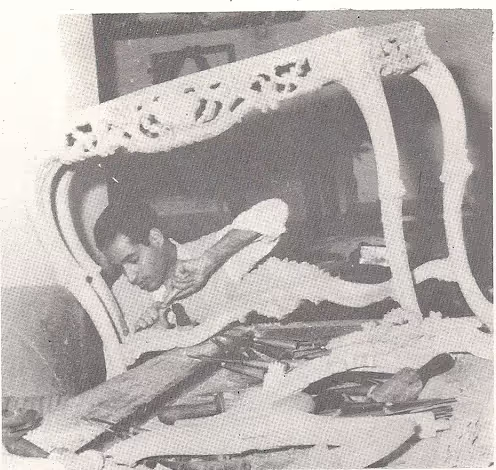

What truly sets Damietta apart is its mastery of “aiwma”,

the intricate art of wood carving and ornamentation.

The art of awima is considered one of the most refined traditional crafts, relying on carving and engraving on wood. It is among the oldest artistic forms that have flourished through the ages, with roots tracing back to the Pharaonic and Islamic civilizations. This art is characterized by precision and high skill, where artisans engrave floral and geometric patterns alongside architectural and artistic motifs, turning each wooden piece into a unique work of art.

For generations, Damietta never struggled with unemployment - Until the start of this decade. Once home to nearly 90,000 furniture workshops, Damietta was the leading governorate in Egypt for furniture production and export, contributing nearly 1% of the world’s classical furniture production.

Now the city resembles a ghost town. Most of these workshops, some over a hundred years old, have shut their doors. In 2020, there was no doubt of the effects of this decline as the Egyptian official statistics agency announced a grim milestone: Damietta had the highest unemployment rate in the entire country. As the furniture industry has been declining, the artisans of Damietta had to leave the trade they had known for decades. Some have kept their shops open. I have talked with some of the remaining shopkeepers.

Twins Mostafa and Mohamed El-Khodary have worked in Damiettas shops since they were eight years old. Out of nine siblings, all in the trained in the trade, they are the only ones that remain in the business, keeping their shops open.

Injuries have become a part of daily life

As I wandered through the streets of the governorate, I didn’t come across a single road that didn’t bear witness to men missing fingers—some missing entire hands. These injuries have become a part of everyday life, so familiar to the eye that people hardly flinch. In time, the people of Damietta became known as “the saw victims.” With the introduction of modern machinery into woodworking and furniture-making, what once offered livelihoods has turned into a source of constant danger. It's estimated that nearly 15,000 craftsmen in Damietta have lost limbs due to outdated and unsafe equipment, such as electric saws and planers. These injuries have grown into a tragic norm among local artisans. Yet, most of them remain outside the insurance system, receiving no compensation from workshop or factory owners. What deepens their suffering is the absence of a specialized hospital to treat such injuries. Many cases deteriorate beyond recovery, leaving victims unable to resume their normal lives.

During my interviews with Damietta's remaining shop owners, I came to hear many different possible solutions. Some suggest lowering the taxes on materials whose prices have been dramatically and constantly rising due to inflation. Others suggest governmental benefits for small furniture-producing enterprises to allow them to compete against the bigger multi-factory companies that dominate the market for nationally produced furniture. Many wish for the means to export their work or limit the import of furniture. From the outside, one could also suggest that the artisans update their style and ways of marketing – by opening organised shops across the country where their work can be showcased and sold.

In recent years, suicide has become a disturbingly familiar headline in the city. After nearly 80% of workshops shut down, leaving thousands of workers jobless, cases of suicide have risen—many following the same haunting pattern. They throw themselves off the city’s highest bridge, leaving behind their national ID cards and shoes. These are not just numbers. They are loud, unanswered alarms, signaling that the crisis is no longer just economic. It is psychological. It is social. These men, once skilled at shaping wood with their hands, are now the ones most in need of a hand reaching out to save them.

None of these ideas was told from a place of hope. Everyone I met had a defeated sense of acceptance towards the state of their craft, the hopelessness filled the air in the narrow streets in what feels like a collective depression.